05:35

Editor's note: This story is part of our continuing World Factory series, which delves into the trajectory of China's economic growth amid a changing geopolitical landscape, the pandemic and a global economic recession. You can read the first, second, third, fourth and fifth stories here.

In a superheated factory mill in the eastern Chinese city of Yiwu, master craftsmen are stirring juice freshly squeezed from harvested sugarcanes. They undulate the long handle of the iron spoons in nine cauldrons, scanning for inconsistencies in the color and creaminess of the liquid. As water evaporates, thick, round bubbles appear while the liquid turns golden brown. The craftsmen then scoop the viscous brown syrup onto a wooden groove to let it cool off.

This is one of the first steps to making many sugar recipes and dessert sauces.

It's also part of a cherished technique for making brown sugar that dates back centuries in Yiwu, once a small impoverished town. Sugarcanes were one of the few major crops that could be grown on its hilly terrains in a humid climate. For generations, making brown sugar by hand and trading it for chicken feathers afforded locals a modest living. This practice, called "Feathers for Candy," was common for Yiwu locals when barter trading was the norm.

"'Feathers for Candy' was very good business in the past," said Chen Peiliang, owner of a brown sugar factory. His father was one of the indigent farmers who often went on such trips starting as a teenager, shaking a rattle drum while carrying two baskets on a yoke, one loaded with brown sugar and the other with chicken feathers. "Once back home, they would single out pretty feathers to make feather dusters or other handicrafts and process the rest to become fertilizers, which would then be applied to the barren paddy field," Chen added.

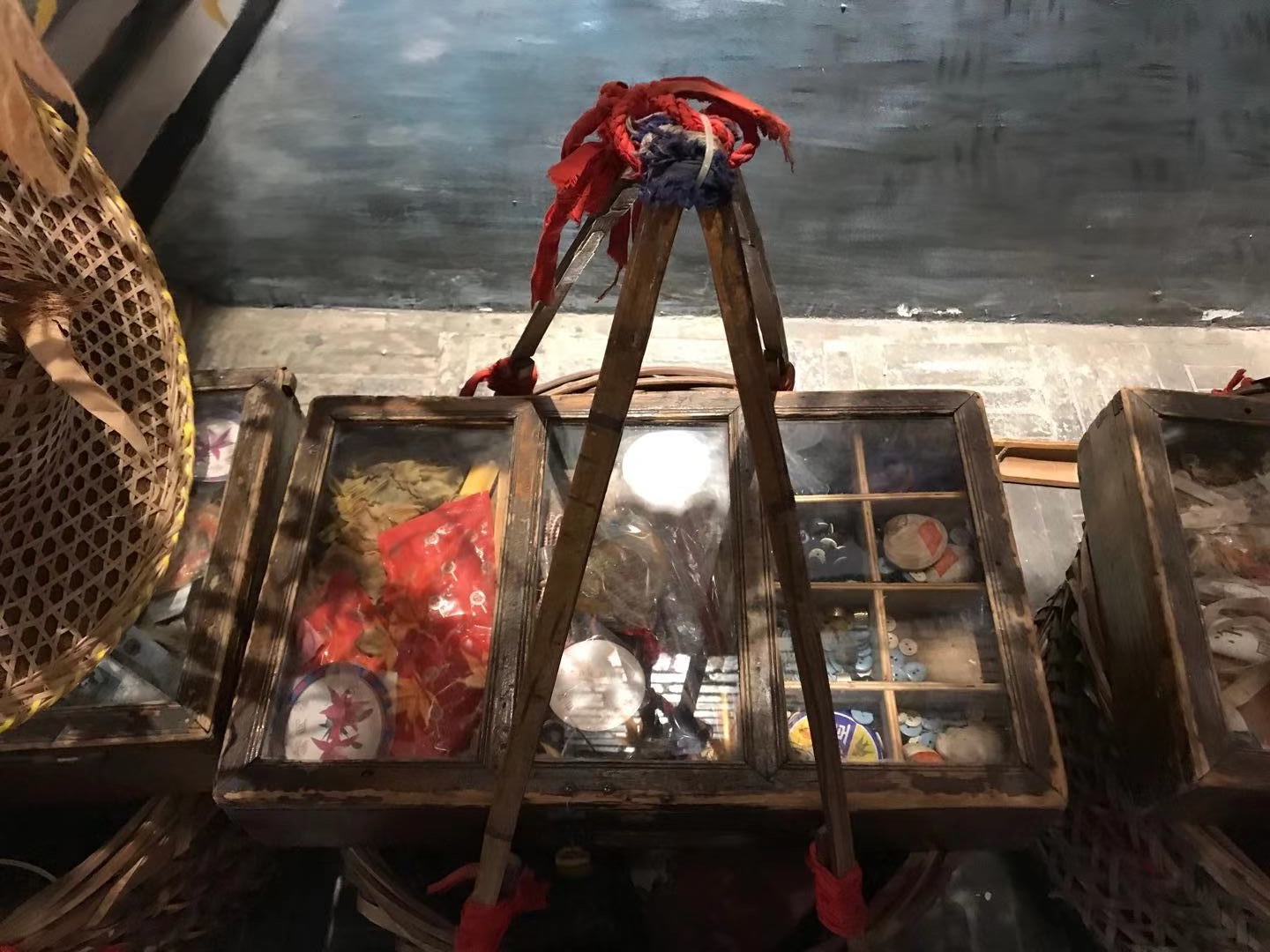

Gradually the two baskets were filled not only with brown sugar products but with commodities and trinkets like buttons, needles and thread, and headwear. As the rattle drum beat, business prospered.

Sugarcanes are seen in the yard of Chen Peiliang's sugar factory, in Yiwu, east China's Zhejiang Province, November 2, 2020. Wang Xiaonan/CGTN

Sugarcanes are seen in the yard of Chen Peiliang's sugar factory, in Yiwu, east China's Zhejiang Province, November 2, 2020. Wang Xiaonan/CGTN

'A poor child, a happy old man'

Chen Peiliang's father Chen Wentian, 83, is a quiet man who likes calligraphy and ink paintings. He remembers his first "Feathers for Candy" trip. "At 18, I carried the pole and walked to Dongyang (a town near Yiwu). Later I left Zhejiang for Jiangxi, Hunan and as far as the northeastern provinces," he told CGTN in his home.

"My father was a tailor and mother passed away when I was little. Life was tough and my father always taught me to be honest and self-dependent.”

A self-taught man, Chen Wentian became a teacher three times but quit each time because the meager income was far from enough to sustain his family of five.

When China ushered in a new era of reform and opening up in the late 1970s, Chen Wentian sensed unprecedented opportunity for him and his peers engaged in small niche businesses over the years.

"My wife and I headed to Qingdao (a coastal city of Shandong Province) to do business in the street market, one of the first fixed-pitch hawker areas in China at the time. We no longer needed to move around," he said.

Things changed rapidly in that age of socio-economic transformation. Nine years later, they moved to Yantai, a city adjacent to Qingdao, because they could have a counter in a department store. They lived there for 20 years working in the clothing business until retirement. "I think of myself as 'a poor child, a happy old man,'" the sanguine senior smiled.

A basket filled with small commodities, used to be carried by local people on a yoke in the past, is displayed at a local restaurant, in Yiwu, east China's Zhejiang Province, November 2, 2020. Wang Xiaonan/CGTN

A basket filled with small commodities, used to be carried by local people on a yoke in the past, is displayed at a local restaurant, in Yiwu, east China's Zhejiang Province, November 2, 2020. Wang Xiaonan/CGTN

'Yiwu is born of brown sugar'

The "Feathers for Candy" profession came to a lull as China opened its doors to the outside world and adopted a market economy. Making and trading handmade brown sugar gradually became a forgotten business, especially when Yiwu set up its first small commodity market in 1982.

Given business acumen, integrity and persistence deriving from the centuries-long "Feathers for Candy" tradition, Yiwu residents quickly built their fortune. Hordes of people from outside the province swarmed in, hoping to make a pile.

"Over 2 million from across the country, about four times the local population, flocked here because here it costs little to start a business," said Chen Peiliang. "People are passionate. The market has expanded from 100 stalls to tens of thousands of shops, from domestic business to international trading."

Yiwu quickly grew to be the world's largest market for small commodities at the turn of the 21st century. In the meantime, the handmade brown sugar industry declined. "In 2007 when I came back from Beijing, I discovered that no one is doing the business except a few villages in Yiting struggling to continue making brown sugar." Chen Peiliang wanted to revive the industry: "It's the root of Yiwu people. The city prospered with handmade brown sugar."

Chinese fried doughnuts made with handmade brown sugar, in Yiwu, east China's Zhejiang Province, November 2, 2020. Wang Xiaonan/CGTN

Chinese fried doughnuts made with handmade brown sugar, in Yiwu, east China's Zhejiang Province, November 2, 2020. Wang Xiaonan/CGTN

But he encountered strong opposition from his father who thought the industry was dying. Chen Peiliang clung to his idea and built a brown sugar factory involving planting sugarcanes, pressing and boiling brown sugar and selling sugar products on the market.

"That was in 2008, our products unexpectedly became a big seller. Everyone is craving for a traditional flavor now that living standards have improved," Chen Peiliang said excitedly.

Besides nostalgia, making sugar by hand can retain the maximum nutrition compared with mass-produced industrial brown sugar. Experiment results show that the handmade brown sugar has a water content below 7 percent and various substances such as calcium, iron and potassium.

The Yiwu brown sugar handicraft was included in the list of China's national intangible cultural heritage in 2014. Chen Peiliang was appointed the inheritor.

Brown sugar syrup is boiling in cauldrons in a sugar factory in Yiwu, east China's Zhejiang Province, November 2, 2020. Wang Xiaonan/CGTN

Brown sugar syrup is boiling in cauldrons in a sugar factory in Yiwu, east China's Zhejiang Province, November 2, 2020. Wang Xiaonan/CGTN

The apple doesn't fall far from the tree

Even before the pandemic struck, e-commerce in China was humming along. Customers would order from their favorite restaurants, get fresh groceries delivered right to their doors, and receive items often on the same day. A few swipes on a popular mobile app like Taobao or Meituan coupled with the ease of digital payments makes a compelling case for the permanent shift to online retail.

"The internet has ultimately changed people's consumer behavior, and brought our market online," Chen Peiliang said. His son, Chen Wanjia, is a sophomore studying e-commerce at Yiwu Industrial and Commercial College. Since his father isn't adept at selling online, he hopes that his son can bring the brown sugar business into the modern era. "My son is a Grade-A student but I think he has the responsibility to pass down our handmade brown sugar," said Chen Peiliang. "We can't just let this cultural heritage go."

Yiwu has an advantage in making the leap to online selling thanks to its various sources of goods, complete supply chains, cheap and fast logistics services, as well as a surge of e-commerce service companies.

Chen Wanjia's college has been training e-commerce talent to cater to this economic transformation.

Chen's teacher Cao Qian has used his family business as a case study. "The pandemic gives a further boost to livestreaming sales. As making brown sugar by hand has a cultural connotation, we considering selling the products by livestreaming the sugar-making process in Chen's factory." Cao Qian talked about the plan with CGTN in Chen Wanjia's studio at the college.

Livestreaming selling, a new frontier of e-commerce which has been all the rage during the pandemic, helps cultivate consumer trust in certain products, Cao believes.

Before, all brown sugar products were sold offline, but now that proportion has shrunk to some 50 percent. Chen Peiliang's son is exploring how to further expand the business with e-commerce know-how, to sustain this national cultural heritage and carry forward the city's business philosophy.

A student at Yiwu Industrial and Commercial College practices selling products via livestreaming, in Yiwu, east China's Zhejiang Province, November 1, 2020. Wang Xiaonan/CGTN

A student at Yiwu Industrial and Commercial College practices selling products via livestreaming, in Yiwu, east China's Zhejiang Province, November 1, 2020. Wang Xiaonan/CGTN

Nonetheless, despite the competitive advantages in expanding this traditional industry in Yiwu, there are challenges. On top of a limited sugarcane yield, craftsmen are disappearing. "Few among the young generation has the craftsmanship spirit because it's tough and there's stigma attached to the profession," Chen Peiliang said.

For Jiang Genxi, a 58-year-old local villager, stewing brown sugar has been his profession for 40 years apart from toiling on the farmland. "During the slack season for farming, usually in the fall, I would come to the factory to boil sugar. I like this job, and I like sweets," he said in his native dialect.

Though the business has evolved, love for the confectionary remains the same.

(Guo Yi also contributed reporting.)

Video director: Zhang Rongyi

Writer: Wang Xiaonan

Voiceover: Zeng Ziyi

Cover image designers: Sa Ren, Qu Bo