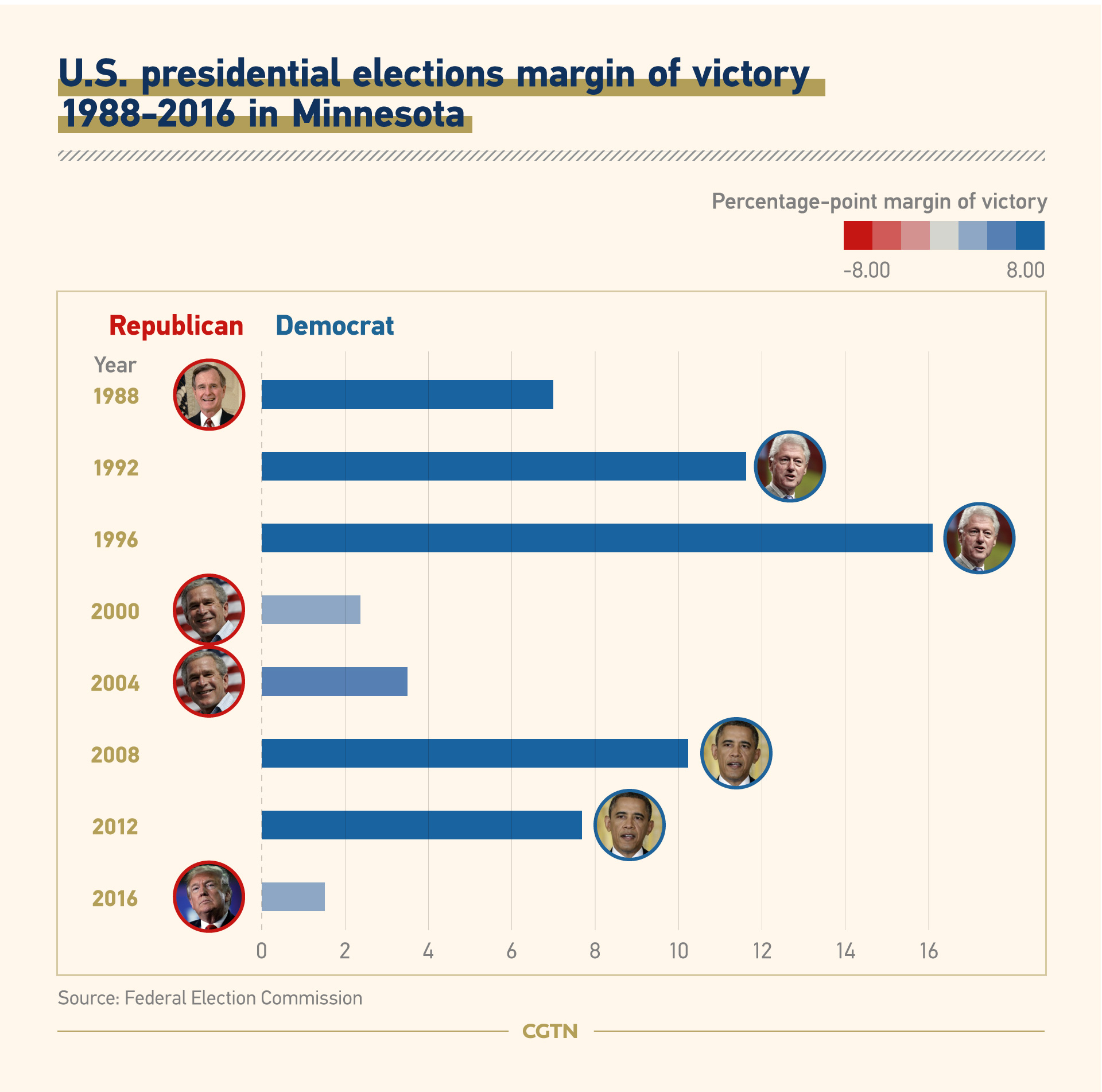

Minnesota has voted Democratic in presidential elections for almost 50 years, but in 2020 Donald Trump sniffs a chance to flip it into the Republican column – a victory over Democratic rival Joe Biden would help offset expected losses elsewhere in the Midwest.

Why does Minnesota matter?

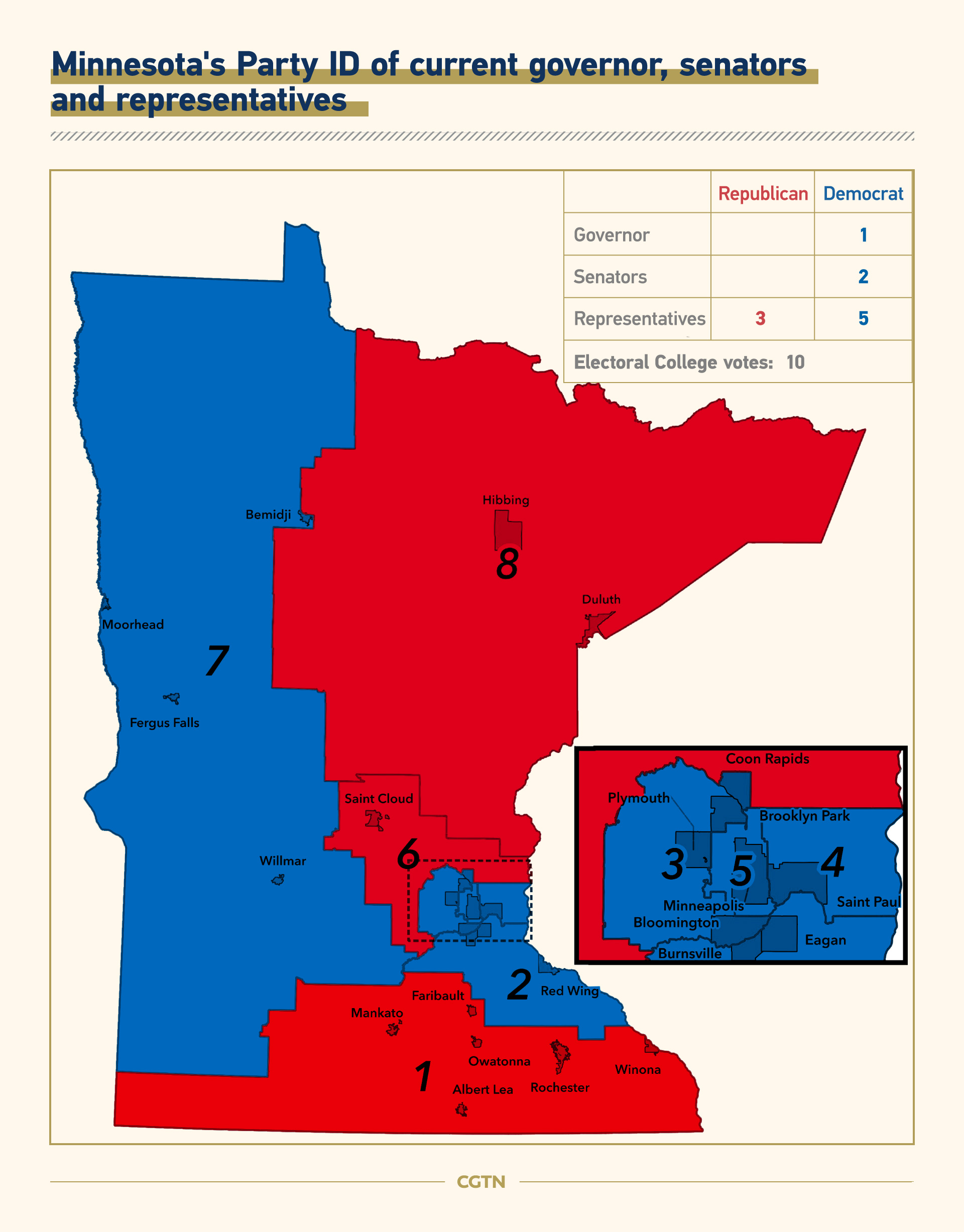

Both campaigns believe Minnesota and its 10 Electoral College votes are in play in this election cycle, with Trump and Biden hitting the trail as early voting began in the state on Friday.

Trump only lost Minnesota to Hillary Clinton in 2016 by 44,543 votes and his repeated visits there reflect his confidence an upset is on the cards. He outperformed predictions four years ago and will need to do so again: the polls this year suggest he faces an uphill battle to overcome Biden.

Watch: 2020 in 120 seconds

"If we win Minnesota it is over," Trump said at a recent rally. If the president were to prove the polls, it would help him compensate for expected defeats in other swing states – though for Biden, a loss in the state would indicate his presidential bid was in serious trouble across the Midwest.

The last Republican to take Minnesota in a presidential election was Richard Nixon in 1972, the sitting governor is a Democrat, as are both senators and five of the state's eight members of the House of Representatives.

That the state is being fiercely fought for matters, but the indicators are firmly on the side of Biden – and he also has a powerful surrogate in Amy Klobuchar, the Minnesota senator, who stood unsuccessfully for the Democratic nomination and has strong cross-party appeal.

Who are the Minnesota voters?

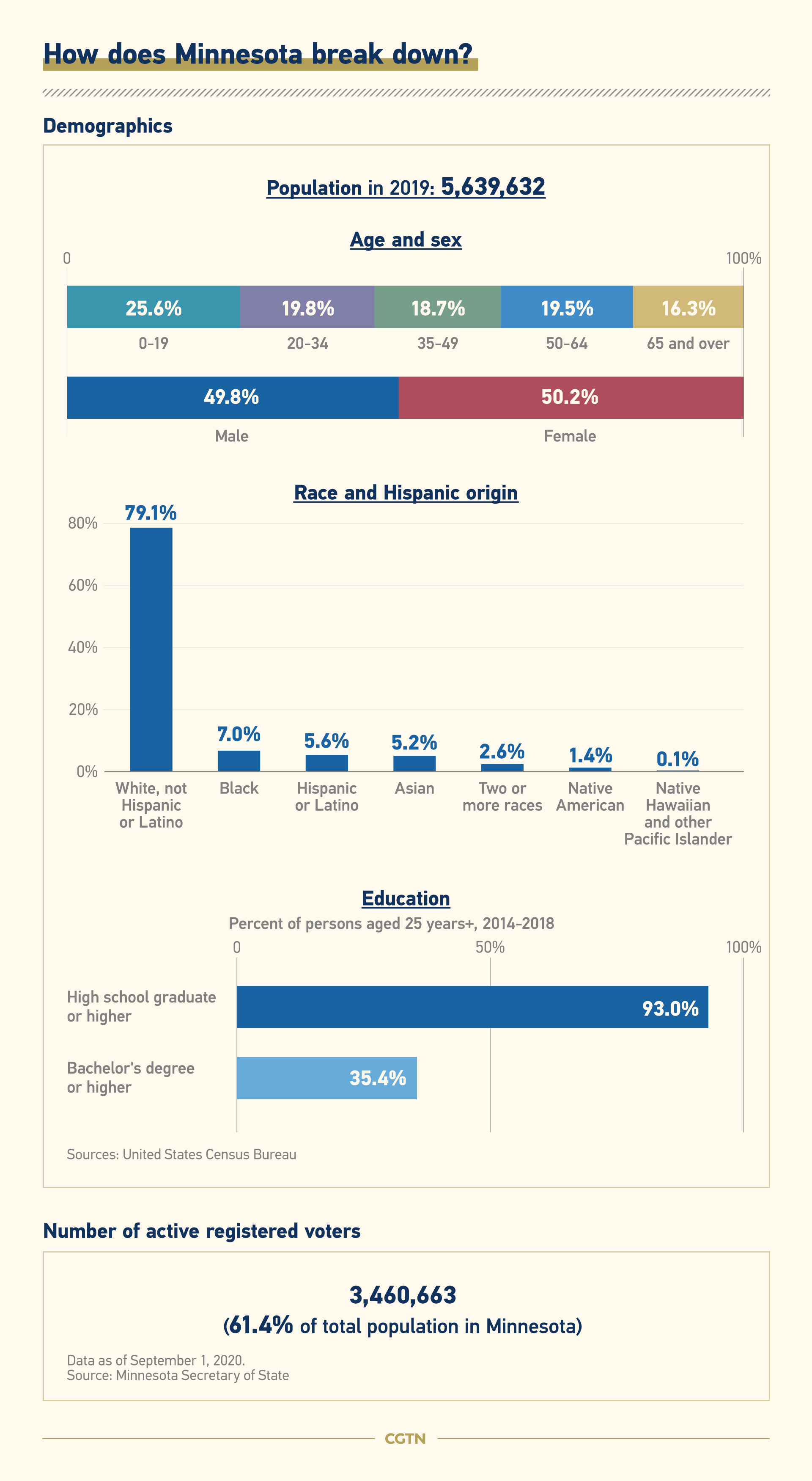

Nearly four in every five people living in Minnesota are white, a narrow majority in the state is female and the proportion of Minnesotans graduating high school and college is higher than the national average.

The president, as elsewhere in the country, struggled with urban voters in 2016, but almost made up for his weakness in large cities like Minneapolis – which Clinton took in a landslide – by winning over swathes of people in rural areas and historically Democratic towns. If these trends intensify in 2020, he has a chance of flipping the state.

Both campaigns are battling for the largely white, rural voters who shied away from Clinton. But white voters without a college degree, who backed Trump heavily in 2016, appear to be much more receptive to Biden and his message: a mid-September Washington Post-ABC News poll found the candidates almost level among that demographic.

Polls suggest there is a stark gender divide in voting intention: the Washington Post-ABC News poll indicated that 67 percent of Minnesotan women back Biden, but a narrow majority of men plan to vote for Trump.

What to watch in 2020

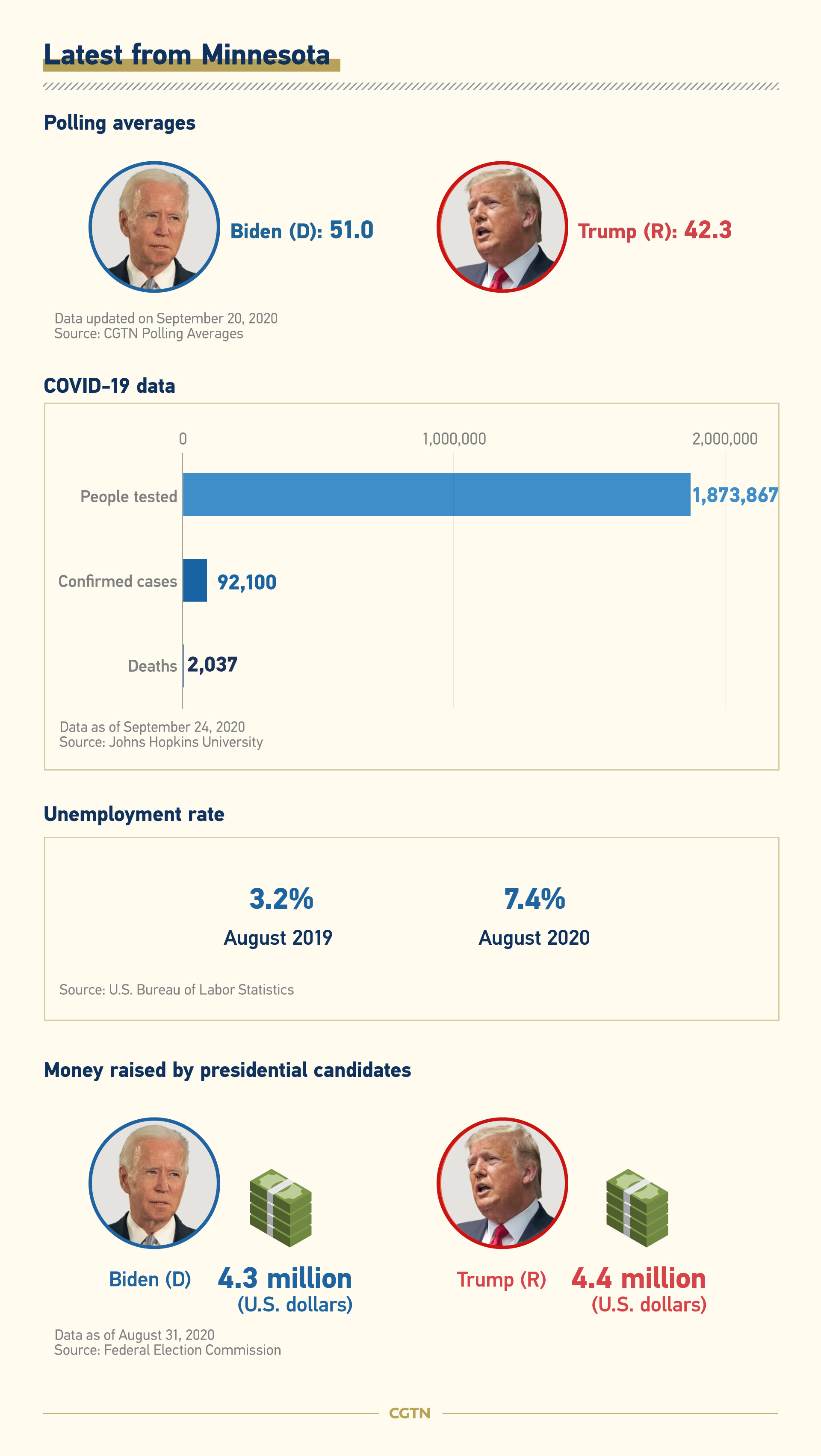

With a week to go until the first presidential debate and six weeks until the election, Biden holds an 8.7-point lead over Trump in Minnesota, according to CGTN analysis of public polling, exceeding his national lead over the president by 1.1 points.

Blue-collar battle: Trump won over many blue-collar workers in 2016, but while Biden's support for trade deals and long history in Washington is seen as a vulnerability by his rival, the former vice president is a very different beast to Clinton. He's built his career on a kinship with the middle-class and unions, and is leaning on it heavily in Minnesota. "Like a lot of you, I spend a lot of my life with guys like Donald Trump looking down on me," he told a crowd in mid-September. "I just have a little bit of a chip on my shoulder because of these guys." The battle for blue-collar workers is the main event.

Law and Order: Since the death of George Floyd in the Minnesotan city of Minneapolis in May and the ensuing protests against racial injustice, Trump has amplified a "law and order" message aimed at suburban voters. Polling suggests white support for the Black Lives Matter movement is dropping, and in Minnesota Trump has used racially-charged language in recent days, telling a nearly all-white crowd in mid-September that they have "good genes," as well as falsely claiming that Biden plans to "get rid of" the police. A similar approach worked for Nixon 48 years ago – but can it be effective in 2020?

Third party sway: Almost nine percent of the votes in 2016 went to third party candidates, a higher proportion than in all but two other states, meaning both Trump and Clinton both won only about 45 percent each. In 2020, the third party contenders appear much weaker than four years ago, so while the voting choices of rural dwellers and suburbanites will be critical, finding ways to attract some of the nine percent into the mainstream could also be important.