The latest ban took the total number of blocked Chinese apps to nearly 220. There are now no Chinese apps in the top 500 most-used apps in India. /CFP

The latest ban took the total number of blocked Chinese apps to nearly 220. There are now no Chinese apps in the top 500 most-used apps in India. /CFP

Editor's note: Abhishek G Bhaya is an International Editor at CGTN Digital. The article reflects the author's opinions, and not necessarily the views of CGTN.

Last week, India yet again banned a number of Chinese apps citing them as risks to its national security. This was the third time New Delhi took such an action since ties with Beijing took a nosedive following the Galwan Valley border clash in June this year.

The latest ban took the total number of blocked Chinese apps to nearly 220. As a result of these measures, there are now no Chinese apps in the top 500 most-used apps in India. That's quite a dramatic shift considering that it wasn't long ago that Chinese apps were among the most popular in India, rapidly expanding their share in the world's fastest growing tech market.

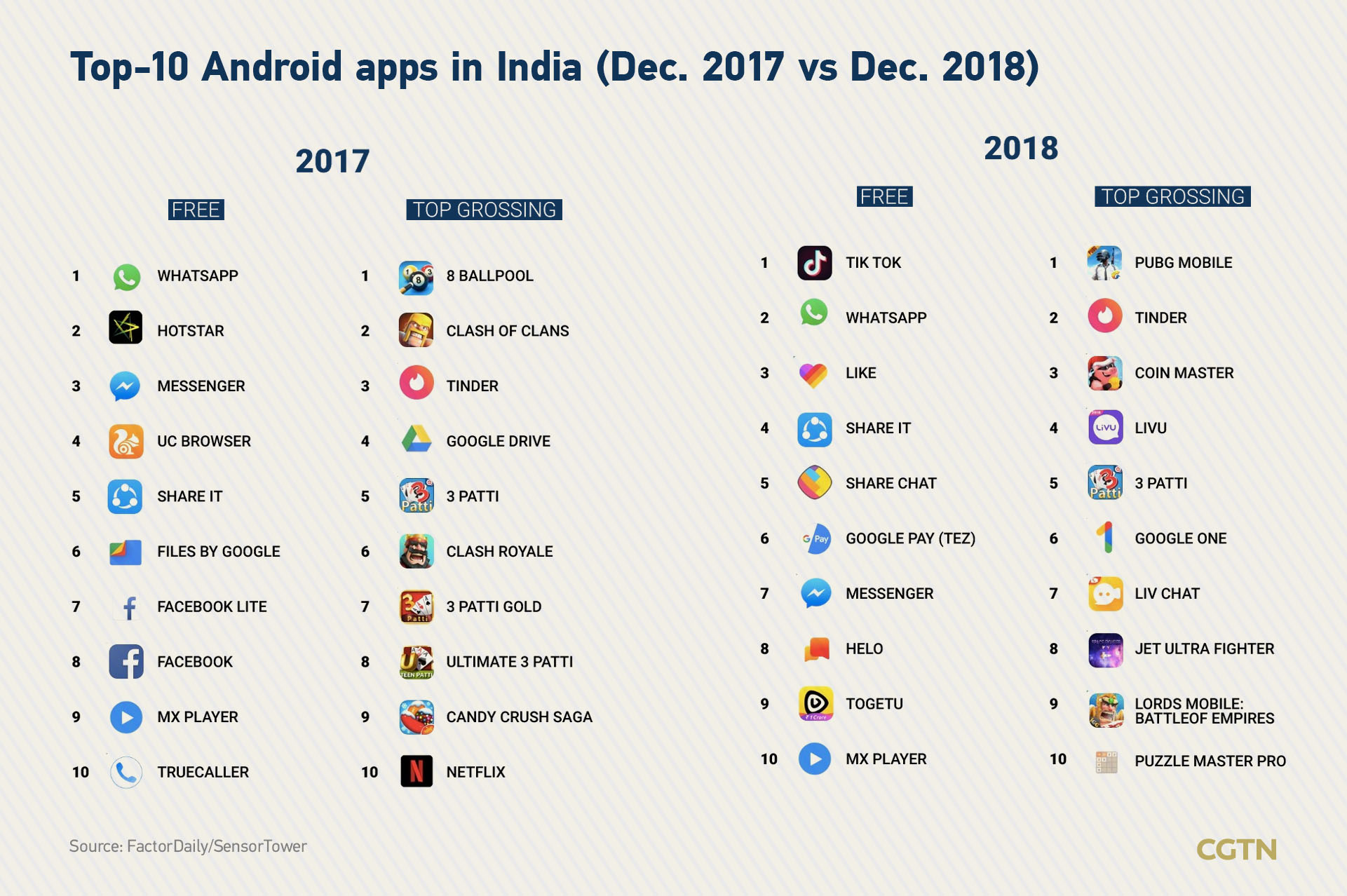

In the first half of this year, Chinese apps held about 40 percent share in India's app market. As many as five Chinese apps featured in the top 10 with Bytedance's Tiktok ranked at No. 1. TikTok, which was downloaded an estimated 600 million times in India, was among the first apps to be banned by New Delhi in late June.

What exactly is driving India to literally firewall the country from Chinese apps? Is it a reaction to the hostilities in the border or a response to an "invasion" of Chinese apps and tech companies? Is it triggered by the rising "techno-nationalism" or is this simply a beginning of India's strategic economic decoupling from China in the long run?

The answer may be "all of the above" but at the core of it lies the deep-rooted trust deficit that has only grown following the border tension.

Read also:

China expresses grave concerns after India banned another 43 Chinese apps

Chinese apps ban by India harms interests of both sides, says MOFCOM

A statement by Indian's Ministry of Electronics and Information Technology on November 24, announcing the latest ban, alleged that the blocked apps were "engaging in activities which are prejudicial to sovereignty and integrity of India, defense of India, security of state and public order."

While the Indian government's press releases do not mention China by name, the list of banned apps – which are all developed by Chinese tech firms – make it abundantly clear who the intended target is.

Expressing "grave concerns" on the issue, China has rejected India's invocation of "national security" as an excuse to "adopt discriminatory restrictive measures" against Chinese firms and apps which "is a serious violation of market principles and WTO rules."

Border factor and trust deficit

Initially, India's action appeared to be a result of domestic pressure on the government to come up with a robust response to the deadly border skirmish. Following the first such ban, announced in June 29, Indian political and economic analyst Mohan Guruswamy told this writer that the decision was "obviously connected to what was happening in the border."

"The reaction to that [border clash] has been pretty severe in India, and the Indian public expected the Modi government to be doing something about it," he reasoned.

03:03

Read also:

Are China and India heading for a trade war?

Himalayan crossroads: A bumpy road ahead for China-India ties

An analysis published by Foreign Policy magazine went further to suggest that Chinese apps became a soft target as the Indian government was compelled to take a stand against Beijing under public pressure. India's "options on trade were limited and potentially self-defeating, while military options were even more dangerous. China's technological exports were a natural arena to turn to – and one in which India could actually impose some damage," the report argued.

Also, India hasn't provided any evidence to prove its claims or show how the Chinese apps are a threat or how their data policies are any different from other popular apps, mostly American, like WhatsApp, Facebook, Twitter, Google and YouTube.

"Every platform, which we have from all over the world, even Indian platform, collects a lot of data. They want to know who you are, where you are, and that provides the basis for their advertisement. Like Facebook, Google, and Twitter, all of them collect data. So, the fact that even Chinese apps such TikTok collects data is not surprising," Guruswamy said in a previous interview.

"Basically, right now, the trust is gone," he said.

Techo-nationalism

A move that may have started as political posturing soon came to reflect the rising "techno-nationalism" in India amid the growing anti-China sentiments fanned by a belligerent media, in the backdrop of the months-long protracted border tension and the worsening COVID-19 situation.

In recent years, Chinese tech companies have made huge inroads in the Indian market, particularly in the smartphone segment. Despite the declining ties, China's top four smartphone brands in India – Xiaomi, Oppo, Vivo and OnePlus – continue to dominate the market with a total share of 75.1 percent as per Q2 data of 2020.

The burgeoning smartphone scene in India saw an explosion of Chinese mobile apps. According to a report from India's tech news portal FactorDaily, by the end of 2018, 44 of the top 100 Android apps in India were developed by Chinese companies, up from just 18 one year prior.

Read also: China, India should attract each other like magnets, rather than 'decoupling'

Banning Chinese apps only hurts the Indian people

With bilateral ties at its lowest in decades, an alarmist "Boycott China" campaign trended on social media highlighting how Chinese smartphones, apps and other products are "invading" India. Some hyper-nationalist Indians even posted videos destroying Chinese-made smartphones, TVs and other products.

In line with the larger global trend of countries fortifying data security and privacy regulations, India was already moving towards protectionist digital policies. The squabble with China only expedited the process with a fervor for techno-nationalism.

"Techno-nationalism has been in vogue in India for a while, which views data as a national asset," Nikhil Pahwa, the founder of MediaNama, an organization that advocates a free and open internet, told The New York Times. He added that the Indian government has had longstanding worries that Chinese companies are dominating local markets and are beating out Indian app developers.

Economic decoupling

The app bans now also appear to be a part of India's larger strategy to decouple from China. India is a net importer from China and has long complained about the widening trade deficit with its larger northern neighbor.

As the global economy faced massive disruption due to the COVID-19 pandemic, India saw it as an opportunity to decouple from China and transform itself into a manufacturing hub with a bigger stake in the global supply-chain networks.

While announcing India's pandemic related economic package in May, Prime Minister Narendra Modi unveiled the "Atmanirbhar Bharat" (Self-Reliant India) mission to see this transformation.

India has also taken other measures that supports the theory that a decoupling is under way. In April, New Delhi passed a legislation requiring government approval for investments from Chinese entities.

Reports suggest India is considering hiking customs duties on 20 products such as laptops, cameras and textiles – a bulk of which comes from China – to restrict imports from China even as Chinese products face clearance delays at Indian ports. India is also eyeing manufacturing of certain products where China has a large share of the global market.

In July, India announced that Chinese companies would be barred from developing roads and highways in the country. New Delhi is also believed to have quietly instructed the two state-run telecommunication firms to stop using Chinese equipment and instead use local providers with questions being raised on whether India will keep Chinese firms like Huawei and ZTE out of its 5G rollout plans.

The overall trend indicates that India's action against Chinese apps is only the most visible manifestation of techno-nationalism and economic decoupling from China.

Some experts feel that India's moves will be counterproductive and end up hurting its own interests. "In trade relations, India is very dependent on Chinese products. [Banning of Chinese] mobile apps won't affect livelihood of common people in India much but if banning escalates to other products, it will also hurt India's interests. Indian government knows this," Lu Yang, a research fellow at Tsinghua University's Institute of the Belt and Road Initiative told this writer.

Beijing hasn't so far retaliated against India's aggressive economic measures including the apps ban, with Chinese Foreign Ministry Spokesperson Zhao Lijian even last week insisting that "China-India economic and trade cooperation, by nature, is mutually beneficial." Zhao appealed that "India should immediately correct its discriminatory approach and avoid causing further damage to bilateral cooperation."

"China is restrained in its action in consideration for the importance of the bilateral relationship, therefore it hasn't taken any retaliation measures against India," Lu reasoned.

In the ultimate analysis, India's latest action is symptomatic of a breakdown of trust in its relationship with China following the border incident in June. It will take an enormous effort on both sides to bridge this trust deficit and ensure that a decoupling is avoided in the long run.